1. Introduction: Envisioning a healthy future for creativity and technology

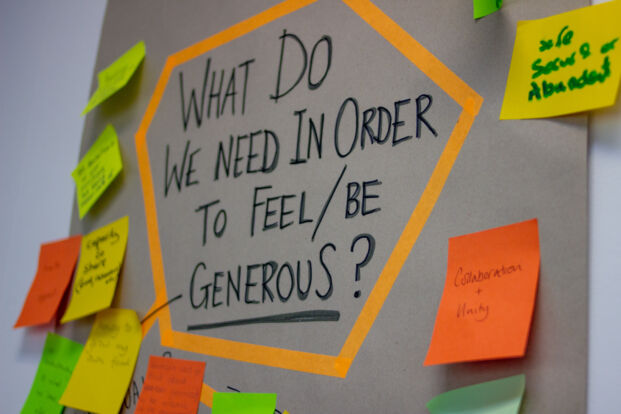

The current creative industry landscape is optimised for practitioners to compete with each other in isolation. We believe that supporting creatives in a way that makes space for collaboration — rather than focusing on innovations built for the ‘creative entrepreneur’ — will foster a healthier, more diverse creative ecosystem.

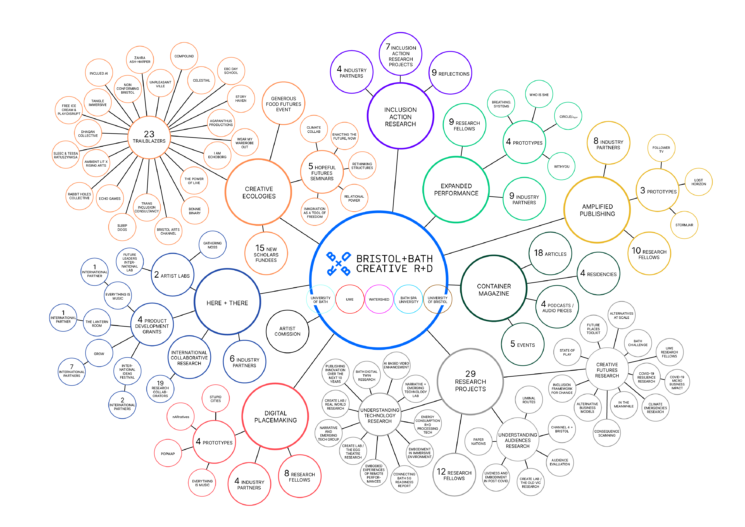

Between 2018 and 2023, Bristol+Bath Creative R+D provided a suite of support to businesses, creatives, artists, and thinkers in our region. Participants received funding to experiment with new and emerging technologies, connect with one another, and develop prototype products and experiences. We also offered business advice, time to carry out research, and supported all participants in showcasing their works to new audiences.

You can click here to learn more about how the programme worked.

Through this five year programme, we developed an environment for the Bristol and Bath creative community which prioritised people over technologies: we wanted to ensure that the community would benefit from research and development in a way that was sustainable and inclusive, without the need for financial returns that often come with grants and funding. This programme was therefore not led exclusively by an imperative for economic growth; there was scope for using responsible innovation to create new cultural, social, and environmental benefits. This people-first approach enabled the community to experiment with new technologies completely on their own terms.

The Bristol+Bath Creative R+D programme consists of four universities (UWE Bristol, University of Bath, Bath Spa University and the University of Bristol) spanning two cities, and a world-leading centre for developing creative applications of new technology (Watershed, Bristol). Together, we wanted to celebrate the region we were based in and find out what worked best for its development.

About this report

This report is for anyone with an interest in thinking differently about how to support creative innovation – policymakers, funders, third-sector organisations, thinkers – in a way that focuses on the people who make and consume creative work, and foregrounds questions of social justice and responsibility.

It contains six sections:

- This introduction

- The challenge: Funding thoughtful and responsible creative technology sets out the current context of creative technology R&D and its funding alongside the wider challenges of digital technology developments.

- Building an inclusive and caring environment for creative technology explores the opportunities of creative technology and how the ethos of ‘creative ecology’ was applied to our programme design. It considers how such thinking might foster connectivity and inclusivity in creative technology R&D.

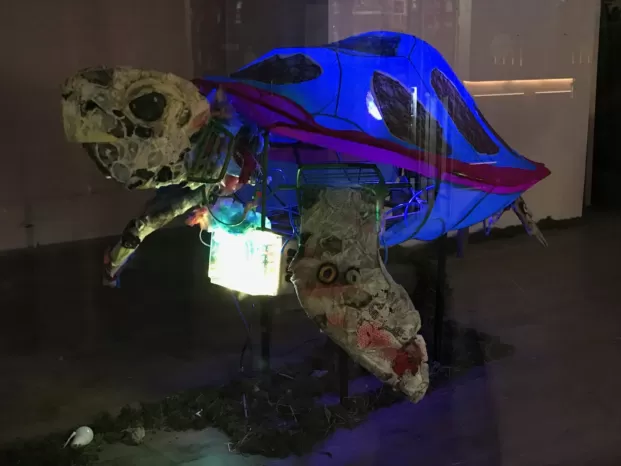

- How are creative technologists responsibly innovating for the future? outlines some of the new ideas and prototypes that emerged from our programme, and how they focus on care, access and inclusion, collective presence, and hybridity.

- Organising for the future shares insights on more equitable economic futures from the programme’s reports and seminars alongside practical toolkits on climate action, inclusion, and responsible business impacts.

- Toolkits for change shares links to a range of resources our community has created to help support innovative R&D in the creative sector.